The Olympia oyster (Ostrea lurida) is the native species that until the late 1800’s was found in abundance in estuaries along the Pacific Coast; roughly extending from Sitka, Alaska to Baha California Sur, Mexico. Around the early 1900’s, being slow growing, susceptible to disease, and possessing a narrower tolerance for water temperatures, and for desiccation stress, the commercial oyster growers also began growing the non-native Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas). By the 1950’s, the Pacific oyster, a species indigenous to Japan, largely replaced the ‘Olympia’ for commercial harvest because of its faster growth capability, and wider tolerance to varying water conditions, though the ‘Olympia’ is still harvested today in limited quantities.

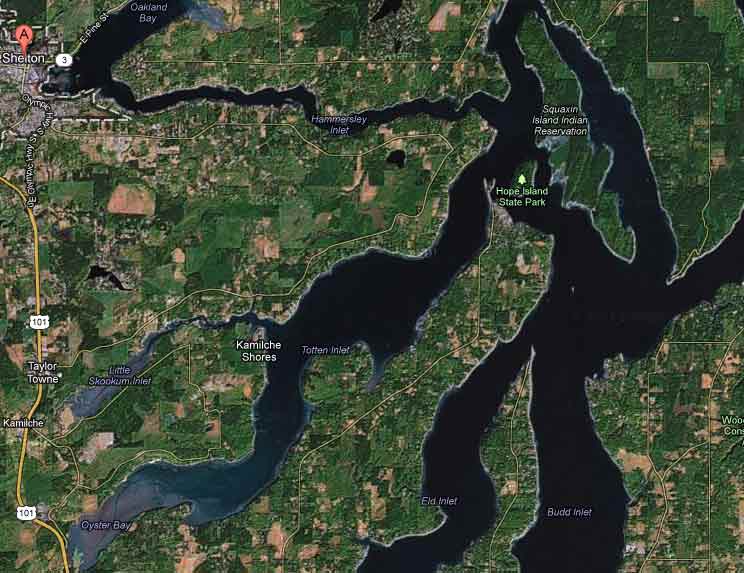

In this episode, Bill Taylor, a 4th generation oyster farmer, and President of Taylor Shellfish Farms shares his families century old connection to the shellfish industry his great grandfather helped develop, and to the South Puget Sound where they continue to successfully farm a variety of oysters (Olympia, Pacific, Kumamoto, and Virginica oysters) and other shellfish.

Although the Pacific oyster is a hardier species than its distant cousin, the Olympia oyster, bivalves in general, are susceptible to water pollution. Their relative health, and ongoing population numbers are a good indicator for the overall health of the bays and inlets that form their habitat.

As Taylor explains in the video, his families farming business, and that of the South Puget Sound ‘Olympia’ oyster industry were nearly wiped out by the local paper paper mill (Rainier Pulp & Paper) that opened in Shelton, Washington, in 1927. The Shelton mill was pumping high levels of sulfites into South Puget Sound, and the oyster beds that were situated downstream. Not until the paper mill closed 30 years later, did the water quality of South Puget Sound begin to recover, and oyster populations increase again, though more slowly in Oakland Bay, because of its proximity and direct path downstream of the mill.

It has been said that “oystering and civilization do not mix well”, as development increases near oyster estuaries, oyster stocks tend to decline.

Oyster farmers must employ sustainable farming practices in order for their businesses to thrive over time. This is a story about a seminal company with a rich history dating back to the late nineteenth century. It’s also an inspiring example of a company that is ensuring the health of its own economic bottom line by working to protect the environmental health of the local community.

Those two ongoing concerns are co-joined at the hip.

Most of the videos featured on Cooking Up a Story were produced, filmed, and edited by Rebecca Gerendasy. Fred Gerendasy contributed as a writer to many of the posts and occasionally as the interviewer. Visit Rebecca Gerendasy Clay – Art and Fred Gerendasy Photography to see their current work.