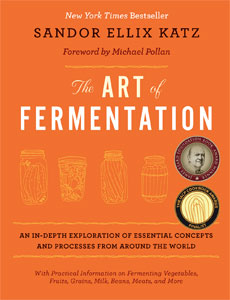

In his most recent book, The Art of Fermentation— Sandor Ellix Katz considers himself a “fermentation experimentalist”. That would appear to be an apt description for his evangelistic passion and encyclopedic knowledge of the fermentation process.

Katz has extensive experience making an almost infinite array of fermentation products, he calls, “ferments”.

As he explains in the video, the process of fermentation occurs when bacteria (and sometimes other microorganisms) partially digest (break down) the carbohydrates in foods, creating a universe of unique flavors and food textures along the way. Fermentation also preserves and extends the life of a food through the byproducts it produces. Fermented cabbage (sauerkraut), for example, remains edible for months (even years), when stored continuously in a refrigerated state.

And that’s one of the central tenets of fermentation; it’s nature’s way of preserving food, and making it desirable to eat in different ways than its original form. Ferments appear to have been made in every known human culture dating back to the earliest civilizations. Mead, for example, considered one the first fermented alcoholic drinks (made from fermented honey), may have originated in northern China as early as 8000 BCE (formerly referred to as BC).

At the recent Portland Annual Fermentation Festival, Katz was one of the keynote speakers where he spent considerable time after his talk just answering questions from the audience. It might be easy to think that fermentation was his first primary interest, but it was not.

As a young adult, Katz moved from Manhattan to rural Tennessee where he and other communal members grew their own food, and lived mostly off the land for 17 years.

Fermentation sprang from his love of food, and the desire to preserve the harvest beyond just the growing season. It was also an opportunity to experiment with fermenting different foods, and to rekindle an early childhood love of pickles.

3 years ago, Sandor Katz moved down the street into his own house where he continues to grow food, make ferments, write, and travel the country giving fermentation workshops to growing audiences.

Katz sees wondrous parallels between the microorganisms in the soil that make farming possible by breaking down organic matter to produce soil fertility, and the microorganisms that make fermentation possible in the fermented foods we eat.

While many people continue to think of bacteria and other microorganisms mainly as an enemy to fear, Katz and other fermentors view bacteria in a rather different light: more, a cherished friend.

Most of the videos featured on Cooking Up a Story were produced, filmed, and edited by Rebecca Gerendasy. Fred Gerendasy contributed as a writer to many of the posts and occasionally as the interviewer. Visit Rebecca Gerendasy Clay – Art and Fred Gerendasy Photography to see their current work.